Discord: A Case Study in Performance Optimization

The techniques used to support trillions of messages

Discord is a permanent, invite-only space where people can hop between voice, video, and text. On the surface, it seems like “just another chat app.” Take a closer look, and you’ll see that it’s really a finely-tuned system that delivers speed, scale, and reliability — the consumer app hat-trick.

Every time you send a message, join a voice channel, or watch a stream, Discord has to route the event to the right place, notify tons of clients, and do so fast enough that it feels instantaneous. That’s easy when your server has 50 people. It’s insane when it has 19 million.

This is the story of the creative optimizations that keep Discord snappy at scale.

Part I: The Actor Model

Before digging into Discord’s implementation details, we need to understand the architectural pattern upon which it’s built: The Actor Model.

Carl Hewitt introduced this idea in his 1973 paper (pdf). Alan Kay embraced it for passing messages in the 80s. Gul Agha formalized its relevance for distributed systems in 1985. Since then, many teams and tools have adopted the model. If you’ve ever read an elaborate sequence diagram or worked in an “event-driven architecture,” you can thank the Actor Model.

What problem does the model address?

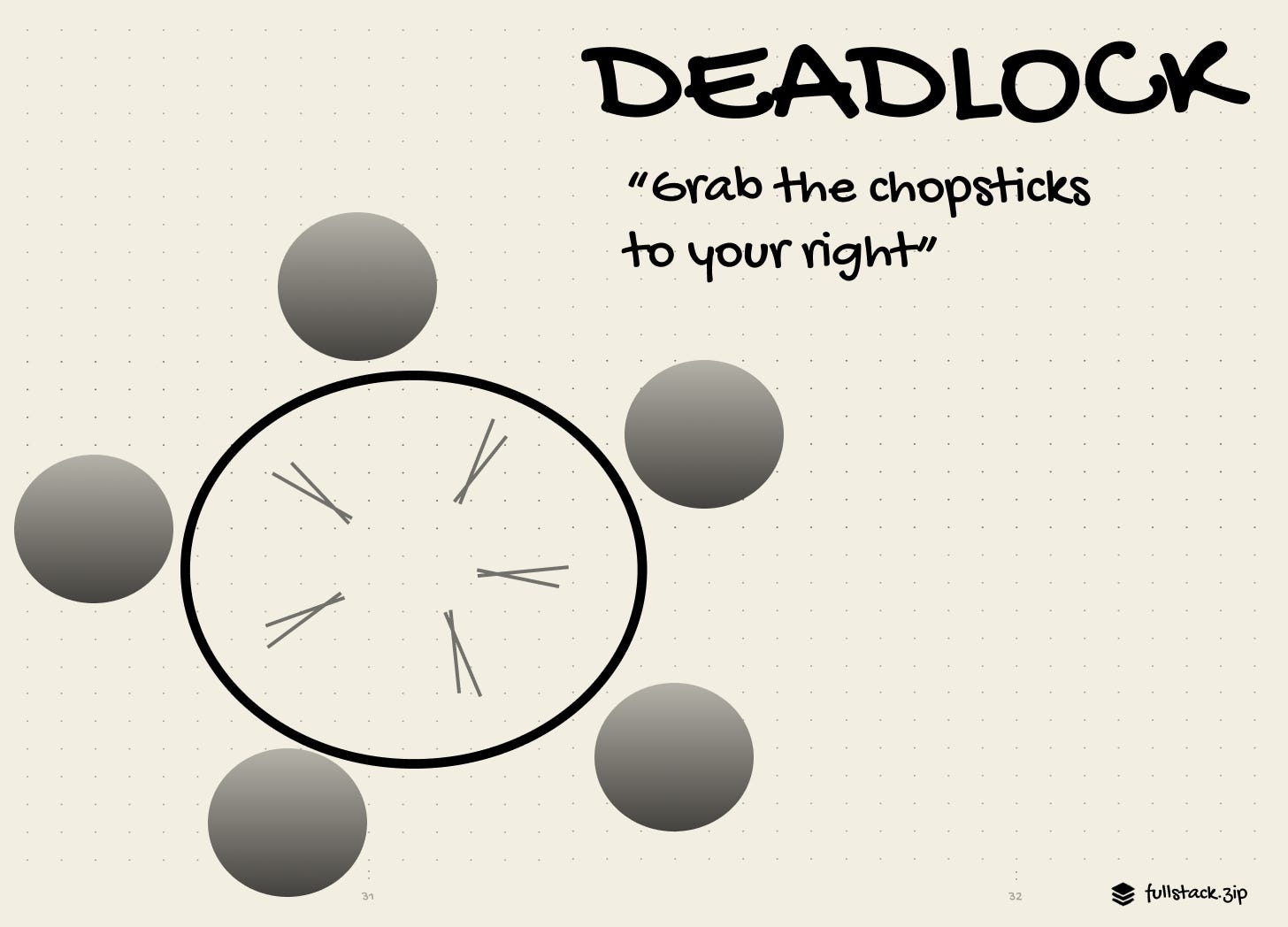

In shared-memory, multiple threads use the same state, which quickly results in race conditions. You can prevent this by adding a data-access constraint: locks. But locks come with their own bugs, like when multiple threads wait for the other to release the lock, resulting in a permanent freeze (deadlock). As systems grow, these problems become bottlenecks.

The Actor Model allows data to be updated more easily in distributed systems.

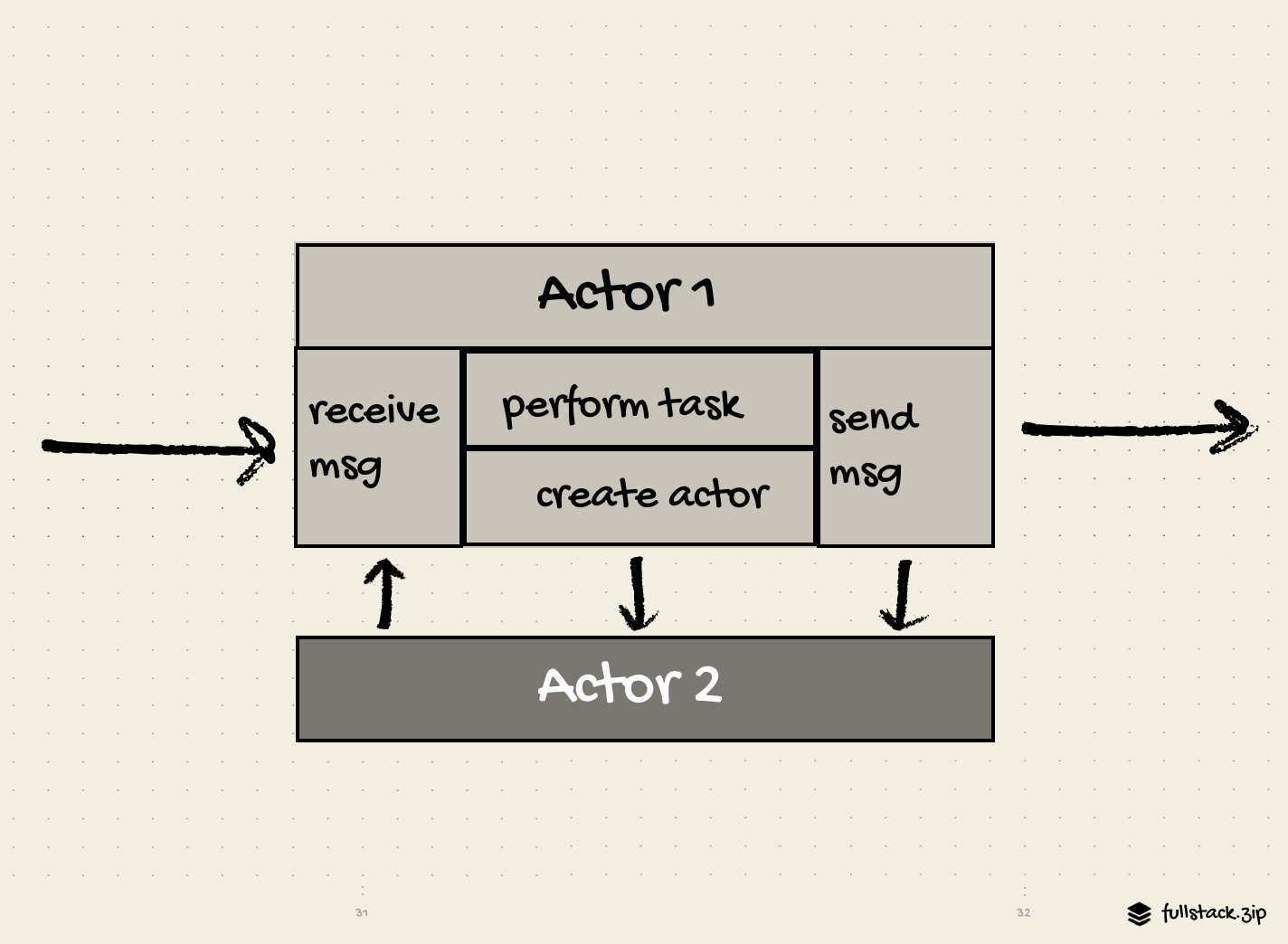

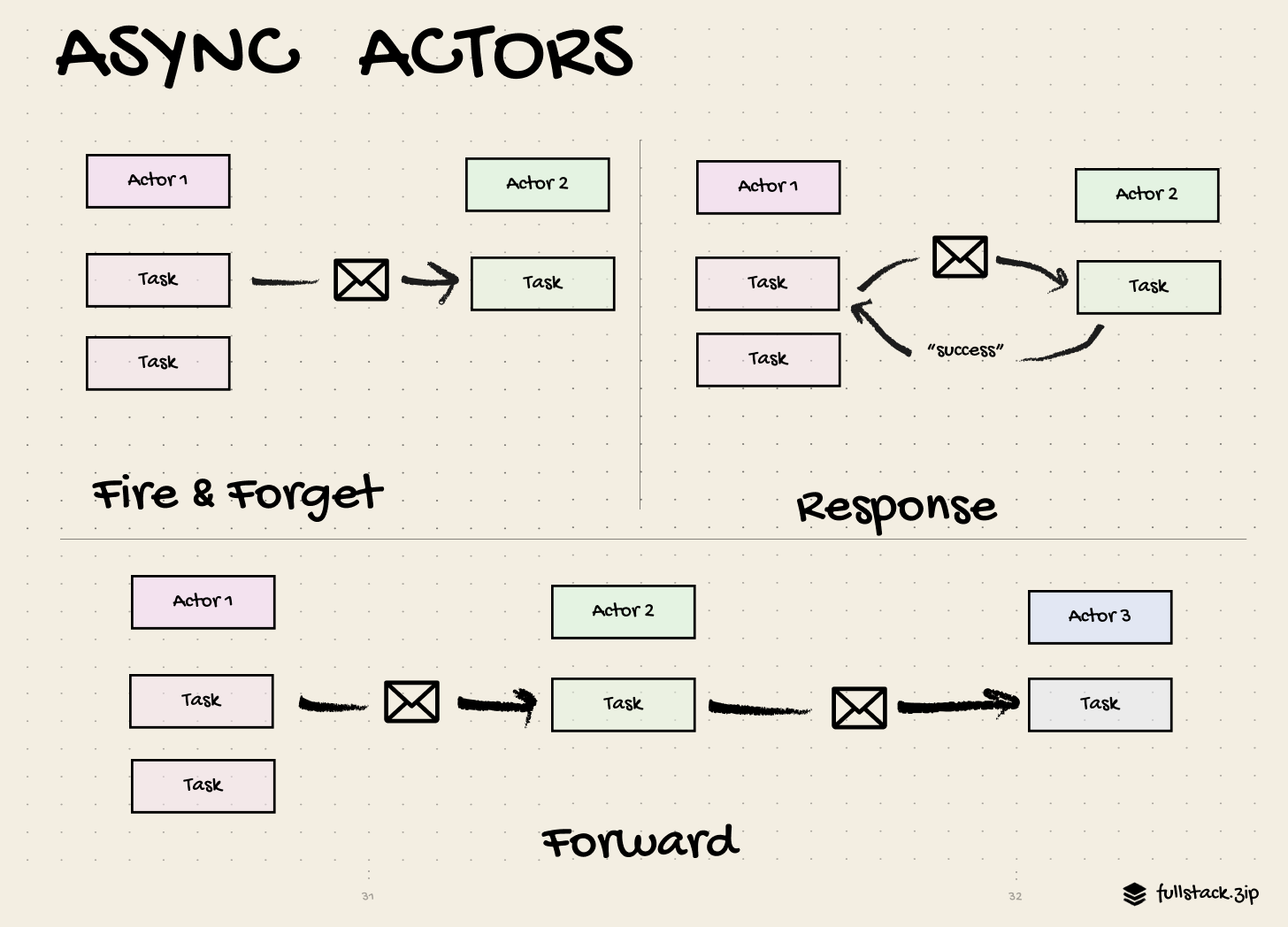

An actor is an agent with a mail address and a behavior. Actors communicate through messages and carry out their actions concurrently. Instead of locks, the Actor Model ensures safe concurrency with communication constraints. The Actor Model can be summarized in four rules:

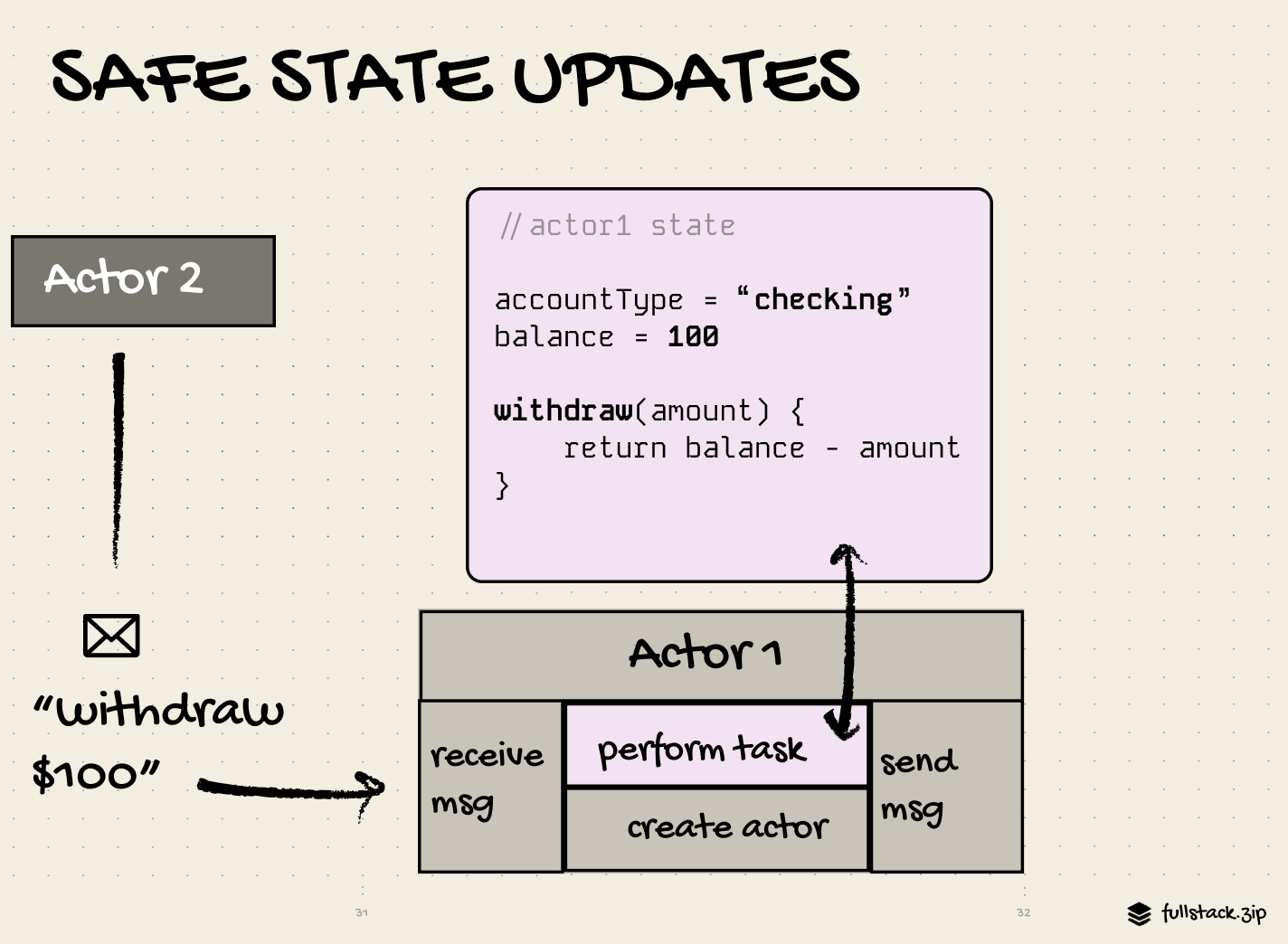

1. Each actor owns its state (no one else can directly mutate it)

2. Actors only communicate through messages

3. Actors process messages one at a time (no race conditions)

4. In response to a message, an actor can:

- Change its state

- Send messages

- Create child actors

Here’s an actor who follows the rules.

actor.start();

actor.send(message); // send to another

actor.subscribe(s => { ...}); // listen to another

actor.getSnapshot(); // cached result from .subscribeAs you can see, actors alone are actually pretty simple, almost pure.

As long as you play by the rules, you won’t have race conditions and lock spaghetti. You also get a few other benefits:

Location independence. The interface means that you can be confident each actor will behave consistently regardless of its location. Doesn’t matter if one actor is on localhost and another is remote. Two actors can even share the same thread (no thread management!).

Fault tolerance. If one actor fails, its manager can revive it or pass its message to an available actor.

Scalability. Actors are easy to instantiate, making them compatible with microservices and horizontal scaling.

Composability. They encourage atomic over monolithic architecture.

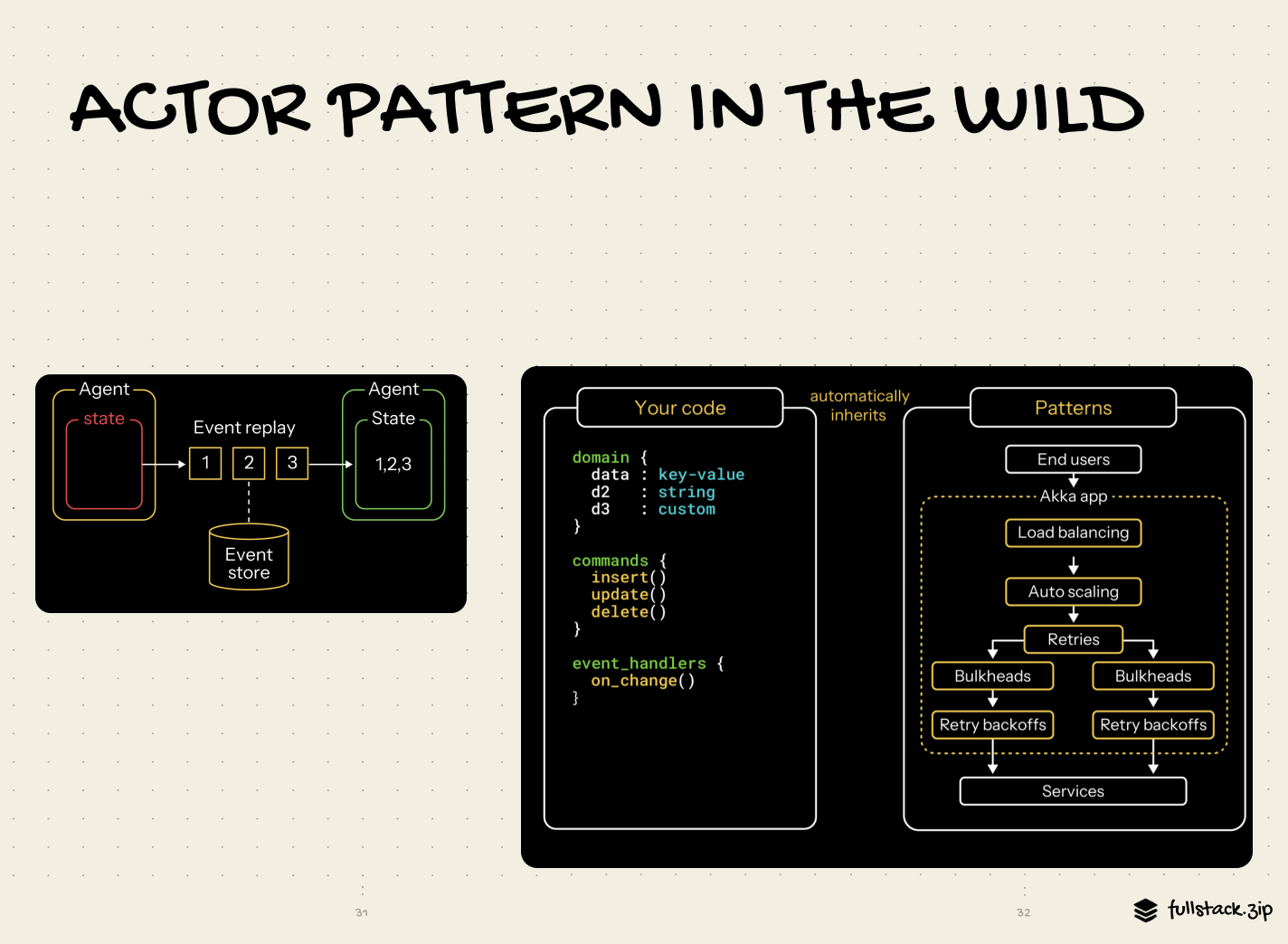

Actors in the wild

There was a quiet period after Hewitt dropped his paper, but adoption has recently taken off in response to our growing data footprint.

Here are a few modern examples of the actor model:

Video editing software sends each setting change so that they are reflected in the draft immediately.

Trading platforms (Robinhood) treat each withdrawal as an isolated actor, which has a function to update an account. Say you have $10 in your account. If you and your wife both try to buy $10 of $GME simultaneously, your app will process the request that arrives first. When the second gets out of the queue, it’ll run the checkBalance statement, see that it’s now $0, and deny it.

AI agents. An agent is an actor. It passes messages (prompts), has internal state (context), and spawns other agents (actors). AI Agents are the perfect use case for the pattern, as Hewitt anticipated. His original paper was called “A Universal Modular ACTOR Formalism for Artificial Intelligence,” after all.

If you squint past the trendy design and jargon on Akka’s site, it looks like the same pitch Hewitt made five decades ago.

Event-driven fabric

Multi-step agents

Persisted state through snapshots and change events

Isolated execution units that maintain their own state

Parallel processing without shared bottlenecks

Unbounded data flows

The next time you see these keywords on a landing page, remember to get out your Actor Pattern Buzzword card and yell “Bingo!”

This concept is relevant on the frontier as well as in the verticals. Cursor’s self-driving codebase experiment took a first-principled journey from unconstrained sharing to a well-defined communication flow between planner and workers. Sounds very similar to actors and managers, doesn’t it?

Is it silly that we’re pretending to be pioneers by rejecting the idea of a global state? Yes, but at least we’re not the only ones who need to rediscover old problems: the agents in Cursor’s experiment also tried and failed to make locks work.

Agents held locks for too long, forgot to release them, tried to lock or unlock when it was illegal to, and in general didn’t understand the significance of holding a lock on the coordination file. — Wilson Lin @ Cursor

Thankfully, the Actor Pattern still works regardless of our willingness to recognize it.

What’s the catch?

It’s really cool that the Actor Pattern has gained relevance over the decades. But the model isn’t without trade-offs. Things become more complicated when you add production necessities, such as a manager, callbacks, promises, initial state, and recovery. The ease of composition will inevitably lead some teams into microservice hell, where they’ll get lost in boilerplate and hairball graphs.

Debugging dataflow bugs can be harder. Although each actor has well-isolated logging, it can be harder to trace a bug across multiple services.

Price. Agents that create more agents is a dream for the engineering team. If that process isn’t constrained, however, it’ll turn into a nightmare for the finance team.

Finally, implementing the actor model in a big org requires education. Pure functions, state machines, event-driven architecture — these are unfamiliar concepts to many. It took me days of research before I “got it.” Many orgs won’t want to dedicate the time to get everyone thinking in a new paradigm, so they’ll fall back to their monolithic habits.

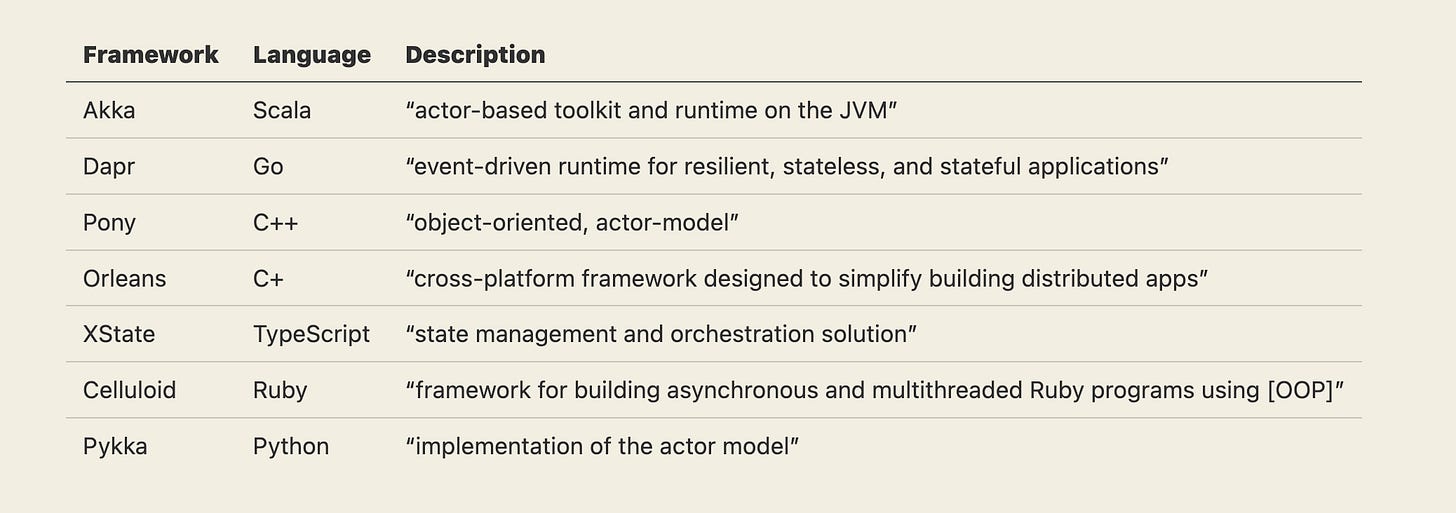

Thankfully, the industry has started bridging the gap between the usefulness of this Actor Model and its adoption complexity by creating languages and frameworks. These preserve the actors’ tenets while making them easier to implement.

Summary

The actor model makes it easier to avoid locks and race conditions in distributed systems. It does this by standardizing communication and data access.

Letting too many things share the same data and chat freely leads to chaos. Think: startup engineer who has to handle info from Slack, hallway requests from the PM, email, and standup. That guy is going to overcommit (deadlock), forget (data loss), and struggle to organize (recovery).

Using an actor model is like requiring everyone to communicate over email. Everyone follows the rules of SMTP (recipient, subject, body) and can only respond to one email at a time (concurrency). In this system, the communication constraints minimize mistakes and conflicts.

All this adds up to a faster, more reliable system at scale. Everyone knows how to talk to each other. They know how to ask for and deliver things. This helps them work autonomously without blocking others.

Having an efficient pattern becomes more important the more distributed a system becomes. As Gul predicted in 1985, more time is spent on “communication lags than on primitive transformations of data.” A team that knows that all too well is Discord, which has successfully instrumented the Actor Model to process trillions of messages without data loss or latency.

Let’s see how.

Part II: How Discord Processes Trillions of Messages

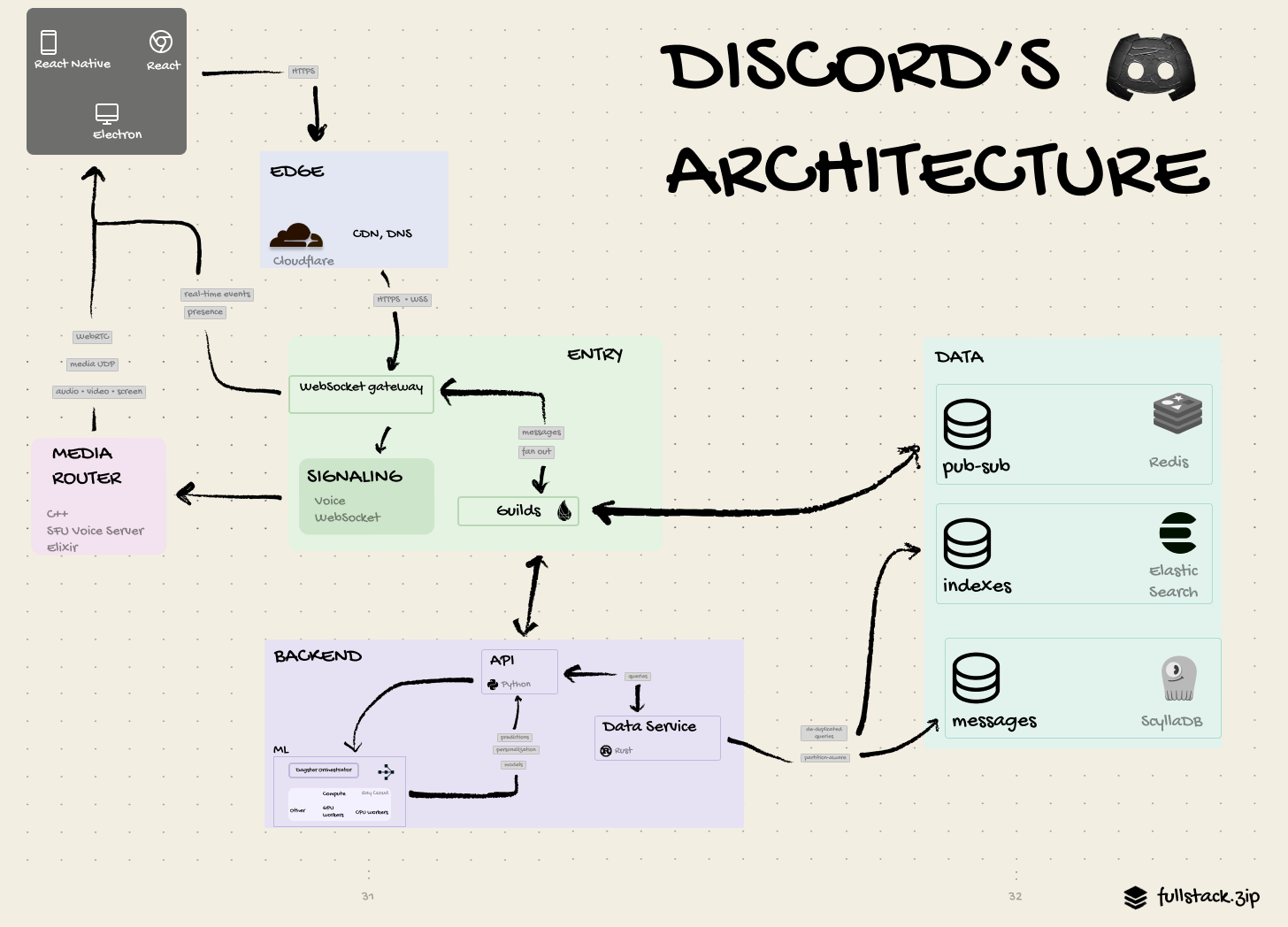

Everything is an “actor.” Every single Discord server, WebSocket connection, voice call, screenshare, etc... distributed using a consistent hash ring.

It’s an incredibly great model for these things. We’ve been able to scale this system from hundreds to hundreds of millions of users with very little changes to the underlying architecture.

— Jake, Principal Engineer @ Discord

Thanks to Discord’s initial target user, gamers, speed has always been an unquestioned requirement. When a message is sent, others need to see it immediately. When someone joins a voice channel, they should be able to start yapping right away. A delayed message or laggy chat can ruin a match.

Discord needed a smooth way to turn plain text/voice data into internal messages and then route them to the correct guild (AKA: Discord server) in real-time.

How data flows

Guilds and users talk over Elixir and WebSockets.

Users connect to a WebSocket and spin up an Elixir session process, which then connects to the guild.

Each guild has a single Elixir process, which acts as a router for all guild activity.

A Rust data service deduplicates API queries before sending them to ScyllaDB.

Background communication happens over PubSub. For example, the Elasticsearch worker consumes events, batches with others, and starts indexing.

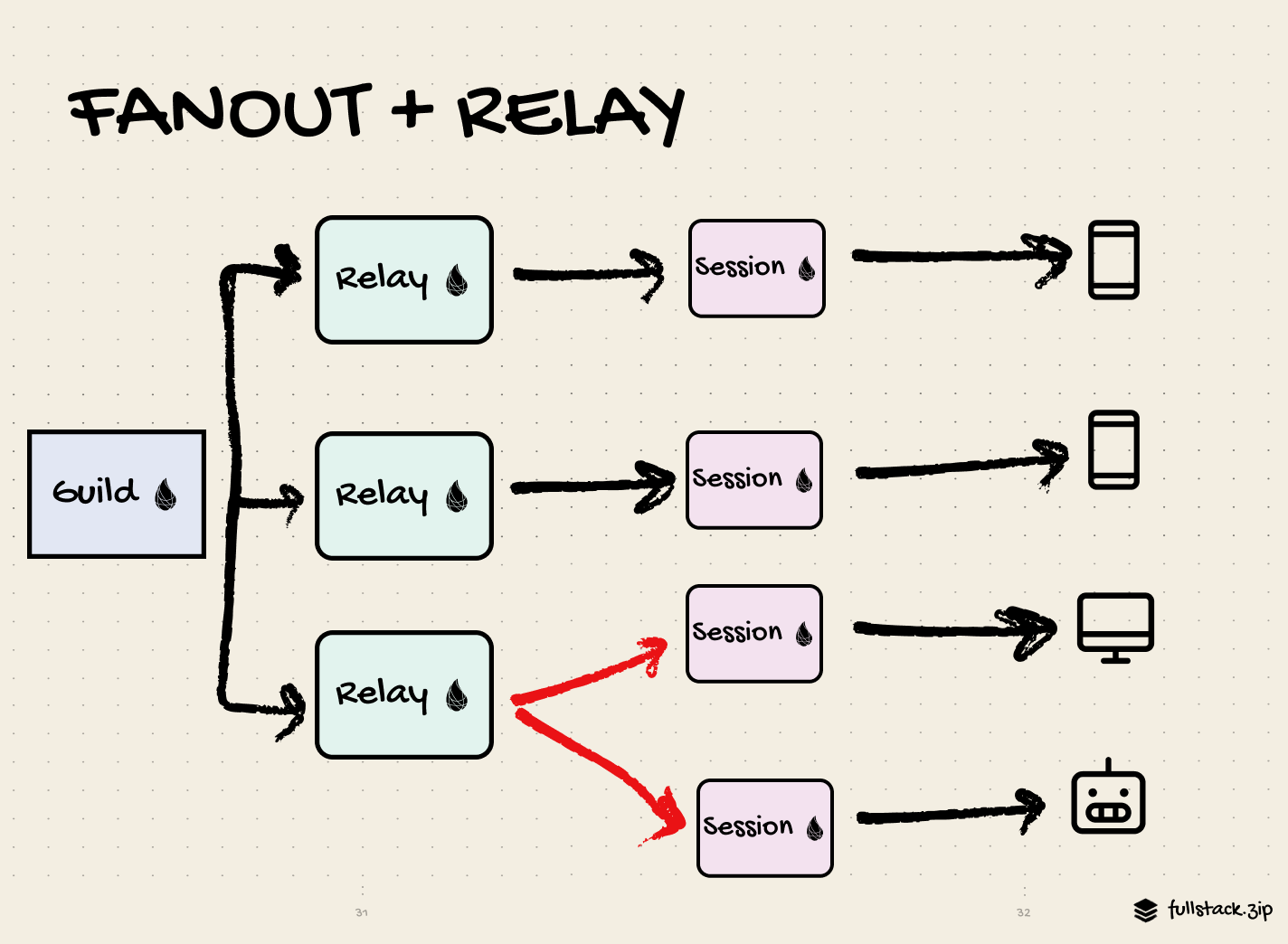

How the fan-out works

“Fan-out” refers to the act of sending a message to multiple destinations in parallel without requiring a response. This is exactly what Discord needed to implement to make their chat feel real-time. When a user comes online, they connect to a guild, and the guild publishes presence to all other connected sessions. Each guild and connected user has one long-lived Erlang process. The guild’s process keeps track of client sessions and sends updates to them. When a guild receives a message, it fans it out to all client sessions. Finally, each session process pushes the update over WebSocket to the client.

In other words:

User ↔ WebSocket ↔ Session ↔ GuildImproving the fan-out

Elixir’s functional implementation of the Actor Pattern allowed it to handle a lot of processes with ease compared to other languages.

# Publishing to other guilds in 4 lines of Elixir. Pretty neat.

def handle_call({:publish, message}, _from, %{sessions: sessions}=state) do

Enum.each(sessions, &send(&1.pid, message))

{:reply, :ok, state}

endThe language’s affordances helped Discord get started easily. But as usage grew, it became clear that they’d need to do more to stay responsive. If 1,000 online members each said, “hello, world” once, Discord would have to process 1 million notifications.

10,000 messages → 100 million notifications.

100,000 → 10 billion.

Given that each guild is one process, they needed to max out the throughput of each. Here’s how they did that:

Splitting the work across multiple threads using a relay

Tuning the Elixir in-memory database

Using workers processes to offload operations (maintenance, deploys)

Delegating the fan-out to a separate “sender,” offloading the main process

Thanks to these efforts, routing the notifications to users in a massive guild no longer became the crippling bottleneck it easily could’ve.

But when one bottleneck is removed, another takes its place. In Discord’s case, their next biggest problem shifted from the messaging layer down to the database.

Part III: Discord’s Hot Partitions

Problem: The Cassandra database was causing slowness

With notifications being routed to the correct guild, and Discord’s API converting those payloads into queries, the last step was to get the data back from their Apache Cassandra cluster. As a NoSQL database optimized for horizontal scaling, Cassandra should’ve scaled linearly without degrading performance. Yet, after adding 177 nodes and trillions of messages, reads were slowing in popular servers.

Why??

In a word: partitions.

Discord partitioned their messages data across Cassandra using channel ids and a 10-day window, and partitions were replicated across three Cassandra nodes.

CREATE TABLE messages (

channel_id bigint,

bucket int, // static 10-day time window

message_id bigint,

author_id bigint,

content text,

PRIMARY KEY ((channel_id, bucket), message_id)

) WITH CLUSTERING ORDER BY (message_id DESC);

That’s fine, but two other factors were at play:

Popular guilds get orders of magnitude more messages than smaller ones. Midjourney has 19 million members, of whom over 2 million could be online at any time.

Reads (search, fetching chat history) are more expensive than writes in Cassandra, due to its need to query its memtable and SSTables.

Lots of reads led to hot partitions, which slowed the messages reads, which slowed the guild. What’s worse, the (valid) use of replication and quorums made other parts of Discord slow, like the upstream nodes that queried the hot partitions. Running maintenance on a backed-up cluster also became tricky due to Cassandra’s high garbage collection, which resulted in many “stop the world” events. Cassandra’s endless config options — flags, gc algorithms, heap sizes — only made it harder to mitigate these issues.

// messages in a channel

[{

"channel_id": 1072891234567890123,

"bucket": 19783, // #announcements channel

"message_id": 1072934567890123456,

"author_id": 856781234567890123, // Midjourney dev

"content": "Hey @everyone, v2 is live. Try it out!"

},

{

"channel_id": 1072891234567890123, // snowflake id

"bucket": 19783,

"message_id": 1072934567890123455,

"author_id": 923456789012345678, // user

"content": "woah, so cool"

}]

Why the partition scheme wasn’t the problem

I instinctively pointed my finger at that 10-day static bucket window and thought, “That’s silly. There’s gotta be a better way to organize the data.”

But is there?

If they dropped the

bucketaltogether, the hot partitions would get even hotter.If they added a random

shardto the partition key, they’d trade hot partition problems with fan-out problems (extra queries, more latency).If they made the buckets smaller (1-day or 1-hour), they’d have to coordinate more round trips.

What if they kept Cassandra for what it’s good at (writes) and moved reads to another solution (cache + index + log)? Sounds complicated.

Partitioning by

message_idwould eliminate hot partitions altogether. But Discord’s primary use case for reads is to get the most recent messages in a channel. Fetching “the last 50 messages in#general” now becomes a huge hunt across every node in the cluster.

Every option either makes it harder to target the data or trades hot partition problems with other problems. So, searching for a more capable database actually seems like a sound first step. If they find one that can cool down the partitions enough to avoid a bottleneck, they could avoid adding more business logic to the data layer.

Thankfully, they found what they were looking for

Solution 1: Switch to ScyllaDB

ScyllaDB is a hard-to-pronounce C++ NoSQL data store that advertises itself as “The Cassandra you really wanted.”

Zing.

On paper, it seems to back that claim up. It’s faster. It’s cheaper. It’s simpler.

How? Here is the gist:

Per-core sharding → more efficient CPU

Per-query cache bypassing → faster queries

Per-row repair (vs partition) → faster maintenance

Better algorithms for scheduling, compiling, drivers, and transactions

No garbage collection

After reading the full Cassandra vs ScyllaDB comparison, I actually felt bad for Cassandra. Like, this was supposed to be a friendly scrimmage — take it easy, guys.

Similar to their early investment in the then-unproven Elixir language, their early bet on Scylla still demanded some work. They had to work with the Scylla team to improve its reverse queries, for example, which were initially insufficient for scanning messages in ascending order. Eventually, Scylla got good enough to support Discord’s workflows, and Discord got good enough at Scylla to casually write the 392-page book on it.

# Optimization scorecard

Better fan-out (service layer): ✔️

Better DB (data layer): ✔️

What else did Discord do to maintain speed at scale?

Turns out, everything.

Let’s look at two more in detail.

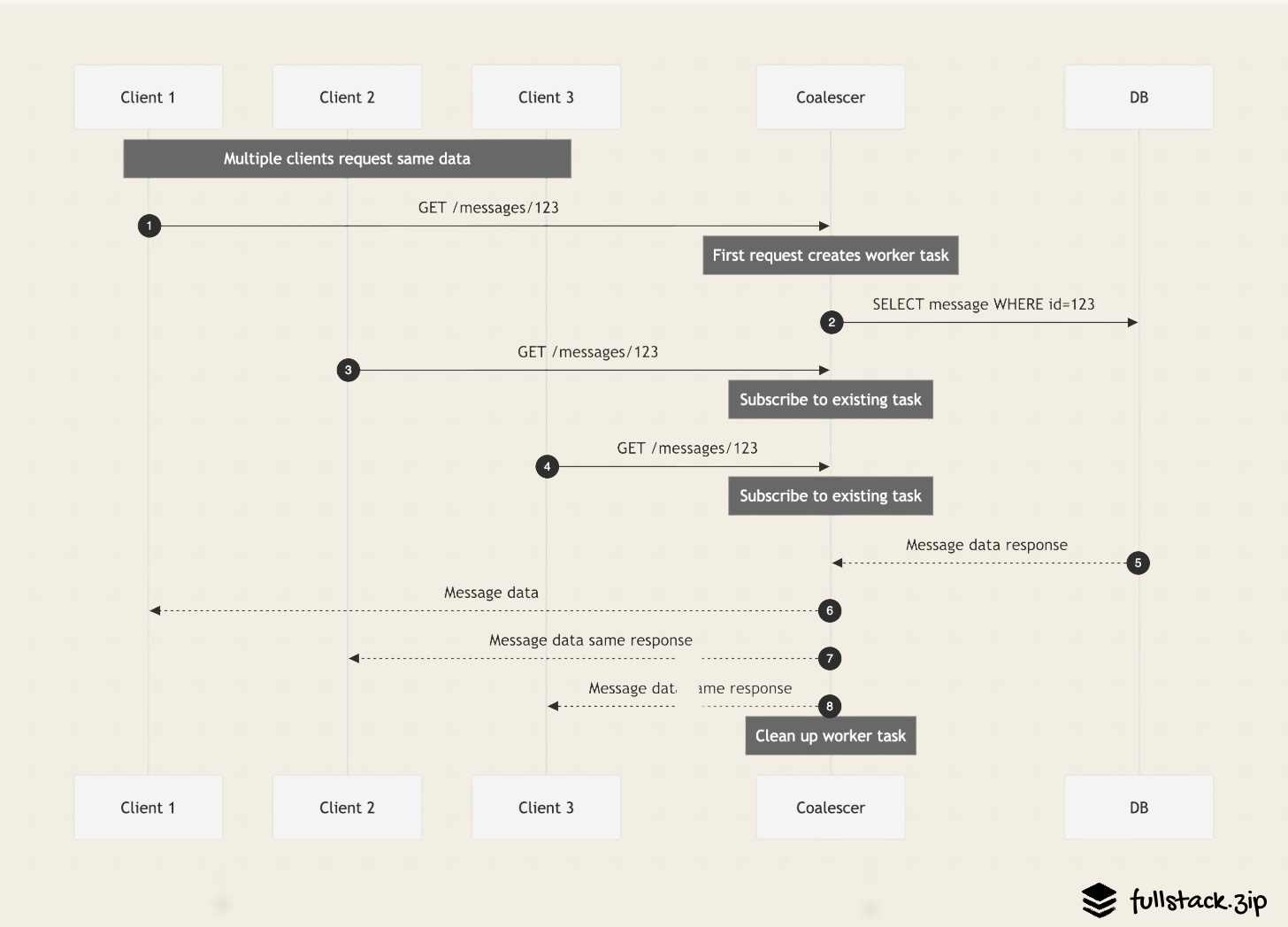

Solution 2: Request Coalescing

Regardless of how compatible your DB is with your app, overriding it with requests will cause latency. Discord encountered this problem with its Python API, which other services could call directly to fetch data from the database. Unfortunately, the message fan-out mechanism resulted in lots of duplicate requests in popular guilds.

This duplicate request problem isn’t unique to Discord, Python, or NoSQL. It’s been around ever since lots of people wanted to access the same information. If you are serving thousands of hits per second, the queue of waiting requests can get huge.

This introduces two problems:

The CPU releases thousands of threads, sending the load sky high (AKA: “thundering herd”).

Users don’t like waiting.

To protect itself from a herd of redundant messages queries after someone spams @everyone in #announcements, Discord introduced a new Rust service, their Data Service Library. When a request comes into the Data Service Library, it subscribes to a worker thread. This worker makes the query and then sends the result over gRPC to all the subscribers. If 100 users request the same message simultaneously, there will only be one DB request.

Request -> Python API -> DB

Request -> Python API -> Data Service Library -> DBThis technique successfully reduced inbound query rate by 10-50x for popular channels and scaled DB connections linearly (one per worker, not per concurrent request). In addition to speeding up UX, it also increased Discord’s confidence in shipping concurrent code, which undoubtedly improved product velocity and reduced bugs.

Most importantly, however, it let them say they rewrote it in Rust.

Meme cred is very important.

— Bo Ingram, Senior Software Engineer @ Discord

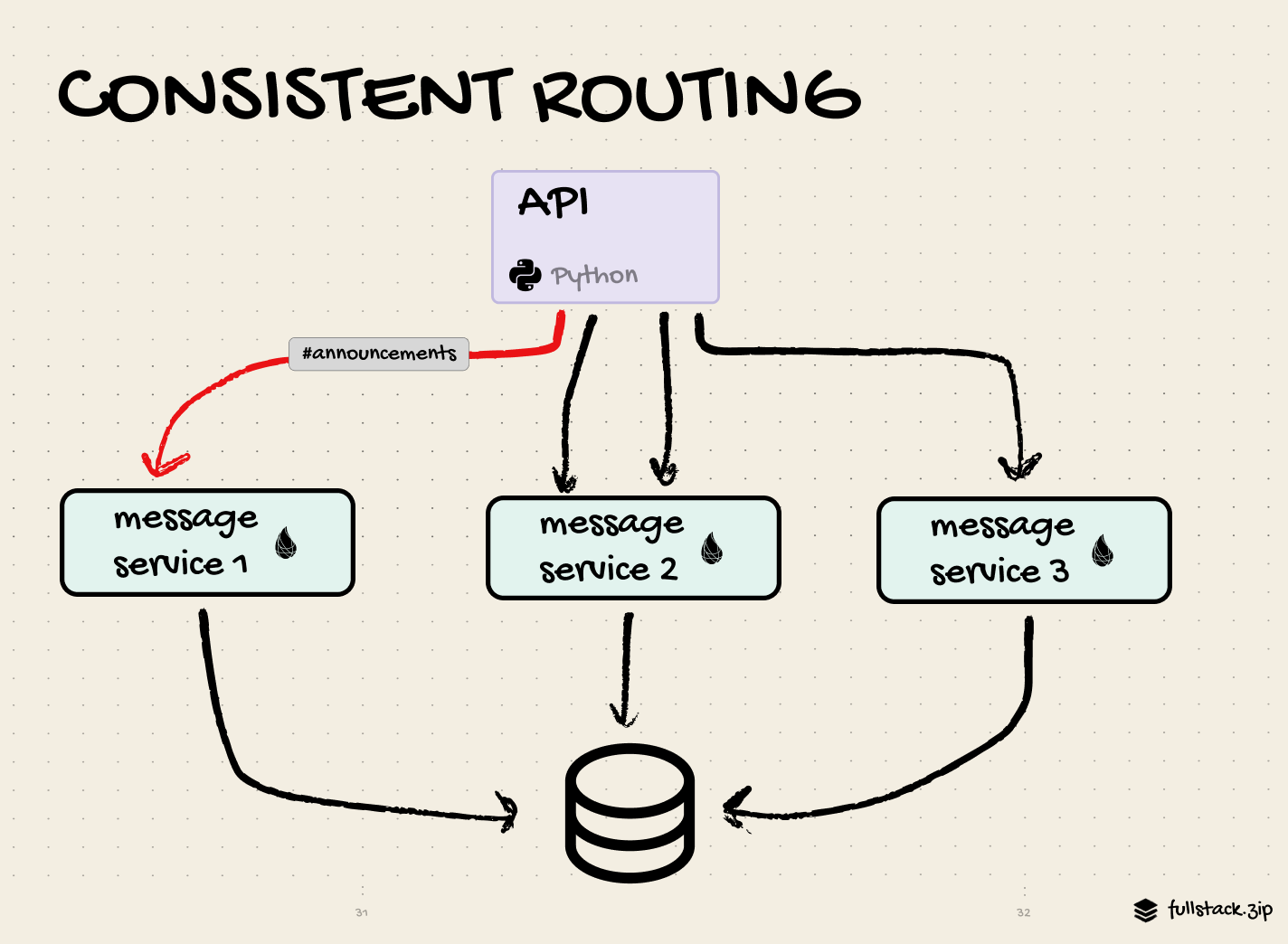

Not a team to rest on their meme laurels, they further optimized request handling by routing each message according to its channel_id. For example, all requests for an #announcements channel go to the same message service. This sounds like it’d be a bad thing, but apparently Rust’s magic lets it handle this case without a sweat. This also makes the request routing from the above point much simpler, as all queries for channel_id=123 hit the same instance’s in-memory cache.

Was the Rust coalescing service overkill? Should they have just used their Redis cache and moved on?

I don’t think so. Caching is about serving slightly stale content. Instead of reducing the total number of requests in the herd, it would’ve simply made each request faster. It also would’ve come with more code to manage.

Caching as a standalone solution to the thundering herd works for apps that don’t need to feel “real-time.” For example, a news site might serve a slightly outdated version of its main page immediately to prevent visitors from having to wait to read something. This buys them time to fetch and render the latest article. The result is faster perceived load times. If they didn’t do this, a thundering herd problem would emerge if 10,000 visitors loaded a trending article at the same time.

Here’s how one HTTP proxy implemented this caching strategy using a simple grace value:

// Vinyl Cache (2010-2014)

// <https://vinyl-cache.org/docs/6.1/users-guide/vcl-grace.html#grace-mode>

sub vcl_hit {

if (obj.ttl >= 0s) {

// A pure unadulterated hit, deliver it

return (deliver);

}

if (obj.ttl + obj.grace > 0s) {

// Object is in grace, deliver it

// Automatically triggers a background fetch

return (deliver);

}

// fetch & deliver once we get the result

return (miss);

}

Key takeaway: When queries are expensive (DB round-trip, API call), in-flight deduplication is cheaper than a distributed cache.

For the record, Discord utilizes this type of caching with their CDN and Redis, but not in the Rust Data Service. (If you’re still hungry for more request optimization nuances, read up on Request Hedging and comment whether you think it would’ve helped Discord’s thundering herd problem.)

Clearly, the request layer was prime territory for optimization, which makes sense for an app that sends many small payloads (a few hundred bytes each). What might be more surprising is where Discord unlocked its next big performance win.

# Optimization scorecard

Better fan-out (service layer): ✔️

Better DB (data layer): ✔️

Better queries (API layer): ✔️

Memes (vibes layer): ✔️

Better disks (hardware!): ??

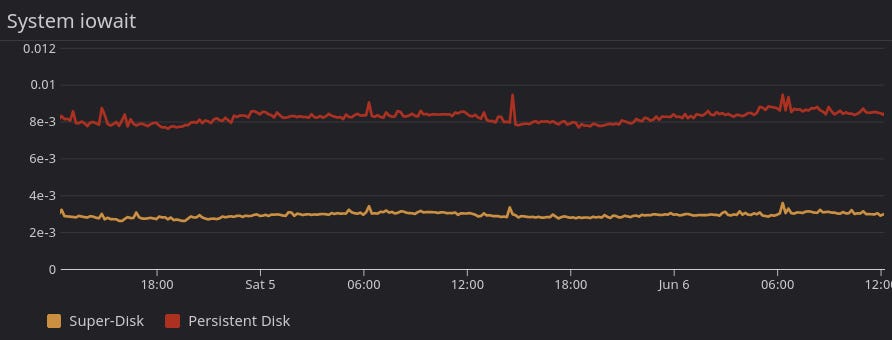

Solution 3: Super-Disk

Eventually, the biggest impact on Discord’s database performance became disk operation latency. This latency resulted in an ever-growing queue of disk reads, eventually causing queries to time out.

Discord runs on GCP, which offers SSDs that can operate with microseconds. How is this even an issue?

Remember that Discord needs speed and reliability. The SSDs are fast, but they failed Discord’s second requirement during internal testing. If a disk holds data in memory and then fails, the data is unrecoverable.

GCP + SSD = 🙅♂️ (too unreliable)

What about GCP’s Persistent Disk option? These are great for duplicating and recovering data. But they’re slow: expect a couple of milliseconds of latency, compared to half a millisecond for SSDs.

GCP + Persistent Disk = 🙅♂️ (too slow)

No worries, surely GCP offers a disk abstraction that delivers the best of both SSD and Persistent Disk.

Nope.

Not only does GCP make you pick between fast and reliable, but their SSDs max out at 375 GB — a non-starter for the Discord DB instances that require 1 TB.

Once again, the Discord engineers were on their own.

They had to find a way to

Stay within GCP

Continue snapshotting for backups

Get low-latency disk reads

Maintain uptime guarantees

So what creative solution did they cook up this time? The “Super-Disk”: A disk abstraction that involves Linux, a write-through cache, and RAID arrays. They wrote a breakdown with the details, so here’s the summary: GCP + SSD + Persistent Disk = 👍 (fast, reliable).

Bonus: 5 More Solutions

We walked through the juicy optimization solutions to the hot partition problem. But Discord didn’t view performance as an isolated priority. Instead, they took every opportunity they found to make things fast. Here is a final roundup of other interesting techniques they used.

Request routing by PIDs (messaging). They optimized how messages are passed between nodes by grouping PIDs by their remote node and then hashing them according to the number of cores. Then they called it Manifold and open-sourced it.

Sortable Ids (data). They used Twitter’s “Snowflake” id format, which is based on timestamps. This let them generate ids without a DB, sort by creation time, and infer when a message was sent by its id alone. The Snowflake project is zipped up in a public archive, but I dug up the good part for you. Notice how the timestamp is used.

protected[snowflake] def nextId(): Long = synchronized {

var timestamp = timeGen()

if (timestamp < lastTimestamp) {

exceptionCounter.incr(1)

log.error("clock is moving backwards. Rejecting requests until %d.", lastTimestamp);

throw new InvalidSystemClock("Clock moved backwards. Refusing to generate id for %d milliseconds".format(

lastTimestamp - timestamp))

}

if (lastTimestamp == timestamp) {

sequence = (sequence + 1) & sequenceMask

if (sequence == 0) {

timestamp = tilNextMillis(lastTimestamp)

}

} else {

sequence = 0

}

lastTimestamp = timestamp

((timestamp - twepoch) << timestampLeftShift) |

(datacenterId << datacenterIdShift) |

(workerId << workerIdShift) |

sequence

}

Of course, Discord had to add its own touch to the ID. Instead of using the normal epoch (1970), they used the company’s epoch: the first second of 2015. I’d normally roll my eyes at this kind of unnecessary complexity. But that’s pretty cool, so instead I grant +5 meme points.

Elasticsearch abstraction (search). Although they don’t store messages in Elasticsearch, they store message metadata and user DMs for indexing and fast retrieval. To support the use case of searching through all of a user’s DMs, they grouped their Elasticsearch clusters in “cells.” This helped them avoid some bottlenecks during indexing. It also helped them index a message by user_id (instead of guild_id), which enabled cross-DM search.

WebRTC tuning (entry). I stayed away from WebRTC here because I covered the basics in the Google Meet breakdown on our YouTube channel. However, Discord does do some interesting stuff at this layer: using the Opus codec, circumventing the auto-ducking on Windows in favor of their own volume control, voice detection, and reducing bandwidth during silence.

Passive sessions (entry): Turns out that 90% of large server sessions are passive; the users aren’t actively reading or writing in them. The team realized they could improve latency by simply sending the data to the right users at the right time. If a user doesn’t have a guild tab open, they won’t receive all of the new messages. But once they tab into the guild, their passive session will be “upgraded” into a normal session, and they’ll receive the full firehose of messages in real-time. This led to a 20% reduction in bandwidth. Amazing example of a big perf win that isn’t technically complicated.

Emojis and lists on Android (client): They were committed to React Native. Then they saw that the custom emojis weren’t rendering well on low-grade Androids. So, they abandoned their original plan and wrote the emoji feature in Kotlin while also maintaining React Native. The worst of both worlds: their architecture is now split between iOS (React Native) and Android (native).

Similar story for rendering lists. They needed to create their own library. Then they adopted Shopify’s. When that stopped working, they created another library that used the native RecyclerView. All for rendering lists quickly on Android.

# Optimization scorecard

Fan-out (service layer): ✔️

DB (data layer): ✔️

Queries (API layer): ✔️

Disk (hardware): ✔️

Routing: ✔️

Ids: ✔️

WebRTC: ✔️

Sessions: ✔️

Emojis: ✔️

This team will tackle any performance problem in the stack with a calm recklessness that I can’t help but admire.

Part IV: Lessons for Engineers

While most of us won’t have to handle trillions of messages, there are some elegant engineering principles we can learn from Discord’s success over the last decade.

Build for simplicity in v1, but design for change.

We examined the migration from Cassandra → ScyllaDB. But they actually started with a DB that was even more unfit for their eventual scale: Mongo. They picked it during the early days because it bought them the time to experiment and learn what they needed. As they suspected, Mongo eventually gave them enough problems (like incorrectly labeling states) to warrant moving to Cassandra. When their Cassandra problems got serious enough, they moved to Scylla.

This is the right way the stack should evolve.

They could’ve never anticipated the bottlenecks at the onset, let alone the right solutions to them (ScyllaDB wasn’t even a viable alternative at the time). Instead of wasting time over-projecting future problems, they picked the tool that helped them serve users and focused on their current bottleneck. They also didn’t overfit their systems according to their current DB, which would’ve slowed down the inevitable migration.

Anticipate the future headaches, but don’t worry about preventing them in v1. Create the skeleton of your solution. Fill in the details with a hacky v0. When the pain happens, find your next solution.

Learn the fundamentals.

Language fundamentals.

Deeply understanding a language helps you pick the right one. When Discord started evaluating the functional programming language Elixir, it was only three years old. Elixir’s guarantees seemed too good to be true. As they learned more about it, however, they found it easier to trust. As they scaled, so did their need to master Elixir’s abstractions for concurrency, distribution, and fault-tolerance. Nowadays, frameworks handle these concerns, but the language provided the building blocks for capable teams like Discord to assemble their own solutions. After over a decade, it seems like they’re happy they took a bet on an up-and-coming language:

What we do in Discord would not be possible without Elixir. It wouldn’t be possible in Node or Python. We would not be able to build this with five engineers if it was a C++ codebase. Learning Elixir fundamentally changed the way I think and reason about software. It gave me new insights and new ways of tackling problems.

— Jake Heinz, Lead Software Engineer @ Discord

There is a world where the 2016 Discord engineers were unwilling to experiment with an unproven language, instead opting for the status quo stack. No one would’ve pushed back at the time. Perhaps that’s also why no one can match their performance in 2026.

Garbage collection fundamentals.

GC’s unpredictability hampered Discord’s performance on multiple dimensions.

We really don’t like garbage collection

— Bo Ingram, Senior Software Engineer @ Discord

On the DB layer, Cassandra’s GC caused those “stop-the-world” slowdowns. On the process layer, BEAM’s default config value for its virtual binary heap was at odds with Discord’s use case. Although it was a simple config fix, a lot of debugging and head-scratching were required (discord).

Unfortunately, our usage pattern meant that we would continually trigger garbage collection to reclaim a couple hundred kilobytes of memory, at the cost of copying a heap which was gigabytes in size, a trade-off which was clearly not worth it.

— Yuliy Pisetsky, Staff Software Engineer @ Discord

At the microservice layer, they had a ‘Read States’ service written in Go, whose sole purpose was to keep track of which channels and messages users had read. It was used every time you connected to Discord, every time a message was sent, and every time a message was read. Surprise, surprise — Go’s delayed garbage collection led to CPU spikes every two minutes. They had to dig into Go’s source code to understand why this was happening, and then had to roll out a duct-tape config solution that worked OK enough…until Rust, void of a garbage collector, arrived to save the day.

Even with just basic optimization, Rust was able to outperform the hyper hand-tuned Go version.

— Jesse Howarth, Software Engineer @ Discord (medium)

The team had to go on so many wild garbage-collecting goose hunts that I’m sure they’re now experts in the topic. While learning more about gc wouldn’t have prevented the problems from happening, I suspect it would’ve made the root cause analysis smoother.

As MJ said, “Get the fundamentals down and the level of everything you do will rise.” If Michael Jordan and The Michael Jordan of Chat Apps can appreciate the basics, then so can I.

Define your requirements early.

The high expectations of their early gamer users solidified the need to prioritize speed and reliability from day one. This gave the young team clarity: they knew they’d need to scale horizontally and obsess over performance.

From the very start, we made very conscious engineering and product decisions to keep Discord well suited for voice chat while playing your favorite game with your friends. These decisions enabled us to massively scale our operation with a small team and limited resources.

— Jozsef Vass, Staff Software Engineer, Discord

At scale, even a “small” feature can turn into a massive undertaking. Calling @here or sending ... typing presence in a 1M user Midjourney guild isn’t trivial. Discord’s need to deliver first-class speed forced it to keep the UX refined and focus on the endless behind-the-scenes witchcraft we discussed here. Had they compromised their performance principle by chasing trends or rushed into other verticals, they would’ve eroded their speed advantage.

This is why, eleven years since the Discord epoch, the app still doesn’t feel bloated or slow.

Although every feature feels like it’s just a prompt away from prod, clarifying your value prop is still crucial. Discord’s was voice chat for gamers.

What is yours?

If you don’t have a good answer, you’ll either ship so slow that you’ll get outcompeted or go so fast that your app becomes slop.

Build a good engineering culture.

Step 1: Have good engineers.

I haven’t seen anyone question this team’s competence. But here’s an example for any lurking doubters.

In 2020, Discord’s messaging system had over 20 services and was deployed to a cluster of 500 Elixir machines capable of handling millions of concurrent users and pushing dozens of millions of messages per second. Yet the infra team responsible only had five engineers. Oh, and none of them had experience with Elixir before joining the company.

Clearly, there were no weak links on this team.

These people are rarely incubated by altruistic companies. Instead, their obsession with juicy technical problems drives their mastery. Then they find the companies that have challenging technical problems and the right incentives. Clearly, Discord has both.

If you don’t have traction, frontier problems, or cash, you’ll have to compete for talent on different vectors. The engineers in your funnel probably won’t be as good as Discord’s, but the takeaway is the same: hire the best you can get.

Step 2: Let them be creative.

Good engineers come up with creative solutions to hard problems.

We saw this in the multi-pronged attack on their hot partition problem. When faced with database issues, lesser engineers would’ve blamed everything on Cassandra and the old engineers who chose it. Then they’d have given hollow promises about how all their problems would fix themselves once they switched to a new DB. Discord instead got curious about how they could make things easier for whatever DB they used, which led them to their Data Service Library for request coalescing.

Same story with the Super-Disk. Investigating the internal disk strategy of their GCP instances isn’t a project that a VP would assign a team in a top-down fashion. Instead, management let the engineers explore the problem space until a unique solution emerged.

Having a culture where engineers can figure stuff out is the corollary benefit to getting clear on your core value. Ideas come from the bottom up, people get excited about the work, and unique solutions emerge. I commend both the Discord engineers for embracing the challenges we discussed and the managers who let them cook.

How creative is your team in the face of tough problems? How can you give them the clarity and space they need to venture beyond the trivial solutions?

Don’t seek complexity, but accept it when it finds you.

Complexity is not a virtue. Every engineer learns this the hard way after their lil’ refactor causes downtime and gets them called into the principal’s manager’s office. The true motivation behind a lot of these changes is, “I’m bored, and this new thing seems fun.” (Looking at you, devs who claim users need an agentic workflow to fill out a form). Complex is challenging. I like challenges. Therefore, let’s do it.

No.

But complexity also isn’t the enemy. For Discord, the enemy is latency. When they run out of simple ways to make their app fast, they come up with creative solutions that, yes, are often complex. Their tolerance for the right complexity is what makes them great. They do the complex stuff not for themselves, but for their users.

It’s OK to complicate things…as long as it helps the users.

As we’ve seen, Discord’s need for speed led it across every layer of the stack, from cheap Androids to expensive data centers. This article documents plenty of well-executed perf techniques along the way — some textbook, some creative. What it really highlights, though, is the power available to teams who commit to helping their users at scale.

Recommendations

The Actor Model

Carl Hewitt (wikipedia)

The Actor Model (wikipedia)

A Feature Model of Programming Languages (sciencedirect)

The Actor Model Whiteboard Session with Carl Hewitt (youtube)

The Actor Model, Behind the Scenes with XState (youtube)

Why Did the Actor Model Not Take Off? (reddit)

Performance Optimization

Fan-Out Definition and Examples (dagster)

How Discord Indexes Trillions of Messages (discord • hackernews • youtube)

How Discord Supercharges Network Disks for Extreme Low Latency (discord)

Pushing Discord’s Limits with a Million+ Online Users in a Single Server (discord)

How Discord Handles Two and Half Million Concurrent Voice Users using WebRTC (discord)

Give the post a "like" if you enjoyed this one.

I loved the deep research, but I want to make sure ya'll actually find this format helpful.